There aren’t two schooling experiences that are identical and each school is a constantly changing universe unto itself. Families and children face challenges on a daily basis in their pursuit of success at school, as well as in trying to fit in the school’s context as a part of the child’s broader social integration. The authors of the Tutoring Model of inclusive education are of the opinion that the gap between school and the community opens when the reasons for learning and social integration difficulties are looked for primarily within parents and children, instead of in the community itself. Fostering the vision of education hinged on a student-cantered educational process, the Belgrade-based Western Balkans Institute has set out on a mission to support the individual characteristic of each school and assist local communities to jointly create supportive environments in which every child is able to recognize and develop its full potential.

There aren’t two schooling experiences that are identical and each school is a constantly changing universe unto itself. Families and children face challenges on a daily basis in their pursuit of success at school, as well as in trying to fit in the school’s context as a part of the child’s broader social integration. The authors of the Tutoring Model of inclusive education are of the opinion that the gap between school and the community opens when the reasons for learning and social integration difficulties are looked for primarily within parents and children, instead of in the community itself. Fostering the vision of education hinged on a student-cantered educational process, the Belgrade-based Western Balkans Institute has set out on a mission to support the individual characteristic of each school and assist local communities to jointly create supportive environments in which every child is able to recognize and develop its full potential.

Conceived as a service of intersectoral cooperation of the key stakeholders in the area of child protection, according to Ms Jelena Nastić-Stojanović, the organization’s Executive Director and the author of the model, the tutoring originated as a grassroots initiative aimed at preventing early school leaving of children who were facing difficulties in and outside the classroom for various reasons. “First of all, I think that we take so many things for granted, and that poses a huge problem”, Jelena started introducing us to the narrative on the foundations of the model whose success relies greatly on the integration of the diverse and distinctive character of each student. “We assume that every family has access to whatever is necessary for their children’s school success, which was exemplified clearly during the coronavirus crisis with the transition to online schooling.”

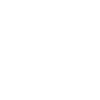

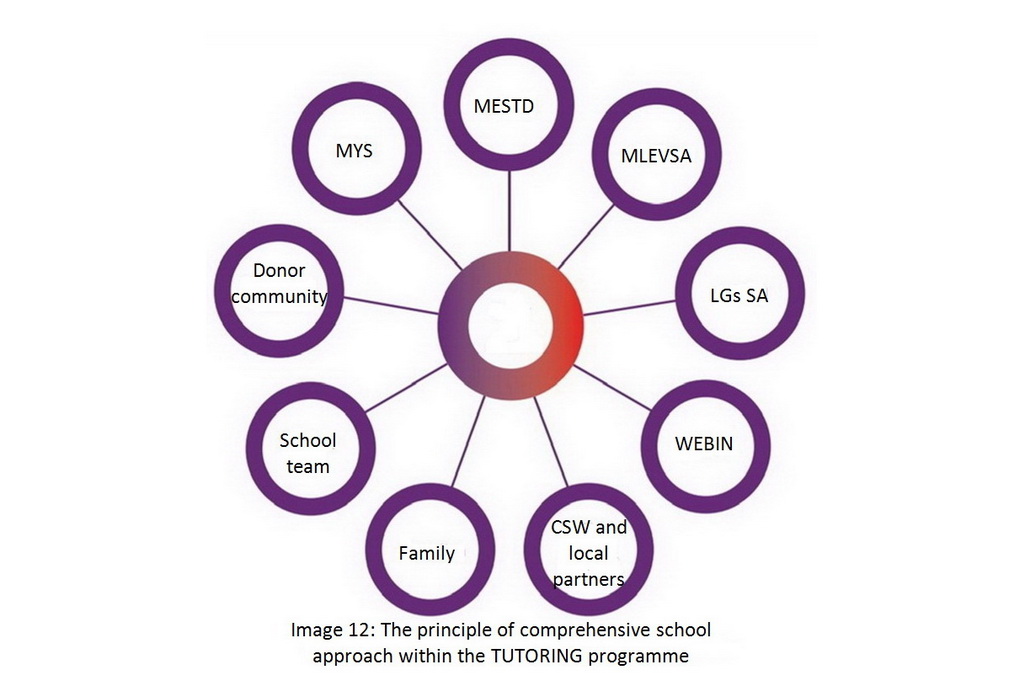

As Jelena explained, the Tutoring Model is founded on solidarity in the development of learning support. The backbone of the model is the provision of learning support before or after school, i.e. the relationship built between the tutor (university student, youth worker or volunteer) and their student (child or youth at increased risk of dropping out of school due to difficulties in learning)*. The progressive nature of the model is reflected in the connections among all child protection stakeholders at the local level, as well as in the insistence on intercultural learning and the sensitivity to cultural and socio-economic context in which the service is provided. The programme includes stakeholders from the local governments, centres for social work, higher education institutions, youth offices and civil society organizations, as well as the school and the parents of the children covered by the programme.

As Jelena stressed, without connecting with concrete communities, the vision would remain just an empty concept. “Parents face significant challenges and the success of the pilot programme required that they build trust in new, previously unknown people, who were now directly involved in their children’s development. They became aware of this and, as a result, we achieved success together.” Emphasizing the specific circumstances of each child, Jelena told a story about a boy who had poor school performance, while at the same time he had remarkable success in geography knowledge competitions. The perceived problem was not in the student’s motivation or intellectual capacities, but rather in the language barrier. “The questions in the knowledge competition were answered by drawing, and that made all the difference”, Jelena described the role of the entire society in the child’s learning experience.

The model was piloted in the 2013/2014 school year, in two primary schools in Raška. Ms Anđelija Roglić, fine arts teacher and the then Assistant Director of the “Sutjeska” Primary School, recollected the beginnings and the first results: “The changes that I find highly valuable are the ones achieved with regard to the children’s motivation and attitude towards the school. The children who had been reluctant to even talk about school for various justifiable reasons not only improved their school performance but also started perceiving school differently, as something of their own.” Through her account of the changes in behaviour and the improvements in socialization, Anđelija affirmed the growth of the feeling of belonging, as one of the fundamental needs of each member of society. “The children continued the tutor-student relationships even outside the pilot programme, which tells us a great deal”, said Anđelija of the programme’s results.

As the key success factors of this model from a school’s perspective, Anđelija highlighted the selection of tutors, the building of a relationship of trust with the students’ parents, and the monitoring of the tutor-student relationships with a view to providing additional support to all involved parties.

The tutors were young people, university students, fresh university graduates and one secondary school student. They were engaged as volunteers, and their selection was conducted in cooperation with the Raška Youth Office. According to Anđelija, one of the key success factors is the fact that sometimes knowledge in itself is not the most significant skill for a tutor-student relationship. Knowledge transferring skills and resourcefulness in dealing with primary-school-age children who lack the necessary support in education are must-haves for a successful tutor. Flexibility in work and sensitivity to students’ circumstances are also critical for tutor-student relationships. Although the tutors signed up for work with one child, one of the tutors worked with two sisters. The elder sister had postponed the start of primary school in order to experience the world of education together with her younger sister. The tutor worked with both of them, and Andjelija says that this tutor-student relationship became an example of good practice of support, since it was a bidirectional relationship, appreciated by the students, too. Likely inspired by this experience, the young tutor nowadays works as a secondary school teacher.

After the selection of tutors and children, the latter among primary school students who faced the most obstacles in education, the next step entailed consultations with the parents. Anđelija says that the parents’ willingness to endorse this type of support for their children was significant and that their involvement was very important throughout the programme. “It was vital to monitor the entire process, so we were constantly in touch with the tutors and parents, making sure that their opinions and needs were acknowledged.”

In just four months of implementation, the results exceeded the expectations of all involved stakeholders. All of the children upgraded their school performance, while the quick improvements in terms of their social integration laid the foundation for long-term benefits.

In the 2016/2017 school year, the programme was implemented in Knjaževac, Raška and Prokuplje, and this year it is carried out in three schools in Vrnjačka Banja.

The fact that the learning principles incorporated in the tutoring model are also applicable nowadays is demonstrated by the piloting of the innovative service of support for students with learning difficulties, which was launched in Raška during the state of emergency. More information about this model, supported by the Serbian Government’s Social Inclusion and Poverty Reduction Unit, and about how online work with students is integrated in it, is available here.

After hearing the experiences of these activists and change-makers in the field of education, one can visualize the outline of the school that represents the groundwork of belonging to a local community. Our ability and willingness to infuse this vision with every story from the community will determine the nature of the educational environments of our future. If we want our communities to look like each one of us, the school is the place where this vision has to become reality.

See the video on the success of the children that participated in the TUTORING programme in Prokuplje, Bela Palanka and Knjaževac in 2016 and 2017.

——-

*Nastić-Stojanović, Jelena, et.al. (2017) Škola u zajednici, zajednica u školi. Zapadnobalkanski institut, Beograd

Government of the Republic of Serbia

Government of the Republic of Serbia

pdf [271 KB]

pdf [271 KB]

Leave a Comment