In the previous article we presented the labour market situation in the European Union, using several key indicators, and showed that the experience of young people varies considerably from country to country. In some countries, young people enter the labour market more easily after completing their education, while in other countries, this school-to-work transition is more difficult because young people not only search longer for the first job but also find lower quality jobs. It should also be pointed out that despite these differences among countries, it can be noted that the position of youth in the labour market in all countries is worse compared to the adult population. For example, in EU countries the youth unemployment rate is almost double the overall unemployment rate. (see Infographic Key labour market indicators: young (15 – 24) and total (15 – 64)). This gap can be attributed to the lack of work experience and the weaker job search skills of young people and to structural problems, including inadequate education and training and overly restrictive regulation of labor markets, and they are the main causes of such high rates of unemployment.

In the previous article we presented the labour market situation in the European Union, using several key indicators, and showed that the experience of young people varies considerably from country to country. In some countries, young people enter the labour market more easily after completing their education, while in other countries, this school-to-work transition is more difficult because young people not only search longer for the first job but also find lower quality jobs. It should also be pointed out that despite these differences among countries, it can be noted that the position of youth in the labour market in all countries is worse compared to the adult population. For example, in EU countries the youth unemployment rate is almost double the overall unemployment rate. (see Infographic Key labour market indicators: young (15 – 24) and total (15 – 64)). This gap can be attributed to the lack of work experience and the weaker job search skills of young people and to structural problems, including inadequate education and training and overly restrictive regulation of labor markets, and they are the main causes of such high rates of unemployment.

This article deals with the transition to the labour market in Serbia and the difficulties young people encounter in this process. The term young person in this text refers to a person aged 15 to 29 years unless otherwise stated. As it will be shown below, the situation of youth in the labour market in Serbia is unfavourable given the high youth unemployment rate and low quality of jobs held by young people. This is of particular importance as research shows that long-term unemployment spells in the early career are associated with long-term spells of unemployment throughout life and lower income in the entire career. In addition, the problems in school-to-work transition of a young person in Serbia negatively affect other life transitions, such as getting married or becoming a parent.

Impact of the economic crisis on youth unemployment rate

Youth unemployment is a serious challenge facing Serbia. The difficult labour market transition in Serbia was also affected by the last economic crisis of 2008, the consequences of which have been felt most by young people. Namely, the experience of other countries shows that at the time of the economic crisis, due to a decline in demand for labour force, firms not only hired fewer workers, but also fired them, often those who were last hired. This is supported by the fact that in 2012 the youth unemployment rate in Serbia was 20 percentage points higher than in 2008. It should be mentioned that young people, even before the aforementioned economic crisis, faced certain problems in the labour market, but this already unfavourable situation was significantly worsened since the onset of the economic crisis. Generations of youngsters entering the labour market since 2009 faced very unfavourable conditions, which led to significant difficulties in the school-to-work transition. Therefore, it is not surprising that in 2015, according to the broad definition of the International Labour Organization, the youth unemployment rate in Serbia was slightly more than 20 per cent , and this rate did not vary significantly between men and women. However, the unemployment rate for young people living in rural areas was about 3 percentage points higher than the same rate of young people living in urban areas, which can indicate that young people living in rural areas are particularly vulnerable groups in the labour market.

Youth unemployment crisis in Serbia

Youth unemployment crisis is a particular challenge facing Serbia, although its social and economic characteristics vary considerably depending on gender and location. The employment crisis is also in a certain aspect a jobs crisis, and it is related not only to the level and duration of youth unemployment on the labour market, but also to the decline in the quality of jobs available for young people.

The youth employment rate in Serbia in 2015 was only slightly higher than 30 per cent , which is about 15 percentage points less compared to the EU countries. The male employment rate is significantly higher than the female employment rate: 38 per cent against versus 25 per cent. This difference can be explained by early marriage and parenthood, which hampers women to enter the labour market. This is due to formal and informal institutional barriers to women’s integration into the labour market, such as discrimination, inadequate family support services, and the norms governing the division of family responsibilities and the behaviour of employers. Also, there are differences in the employment rate for young people living in urban and rural areas, where this rate for young people living in rural areas is higher about 6 percentage points compared to young people living in urban areas. It’s the same as in the case of young women, the chances young people living in urban areas have are defined by institutional structures, customs, norms, and they lead to the fact that they are less likely to opt for longer education, causing their early entrance into the labour market and consequently a higher rate of activity.

Status in employment

In Serbia, in 2015, by status in employment , 4 in 5 young people worked for wages, 1 in 10 young people was self-employed, while as many as 1 in 9 young people was contributing family worker and received no remuneration for his/her work. Contributing family workers as a subcategory of the employees who help family members in family business, but not being paid for it, began to disappear in the EU countries, while in Serbia about 10 per cent of young people fall into this category. Also, nearly 8 per cent of young people have the status of self-employed, which is another devastating fact, since according to the study Analysis of the Regulatory Framework of Entrepreneurship in Three Most Promising Activities, with Proposed Simplification of Business Procedures for Young Entrepreneurs, 40 per cent of young people want to start their own business. This indicates the existence of significant constraints making it difficult for young people to realize their entrepreneurial aspirations . This situation is even more dramatic in the Serbian labour market having in mind that the self-employment rate for young men is twice that of young women.

Qualifications match

The success of the transition from school to work can be also analysed on the basis of the match of qualifications between the job held by a person and his/her educational qualifications. It is known that in countries with a pronounced employment crisis, some young people accept jobs for which they are overqualified, i.e. the jobs for which educational qualifications go beyond qualifications required for them. This is the situation in Serbia, where according to the data for 2015, one fifth of young workers are overqualified, and where a quarter of young women and one seventh of young men are overeducated for their jobs. This observed mismatch is particularly noticeable among young employed women. This can be related to the fact that it is harder for young women to find employment than for young men, and therefore they are forced to accept jobs that are below their educational qualifications. The greatest qualifications mismatch can be seen among elementary occupations, i.e. those occupations that require completed primary education. Namely, 78 per cent of young people who performed these elementary occupations were overqualified, that is, they had a higher level of education than required to adequately perform the job.

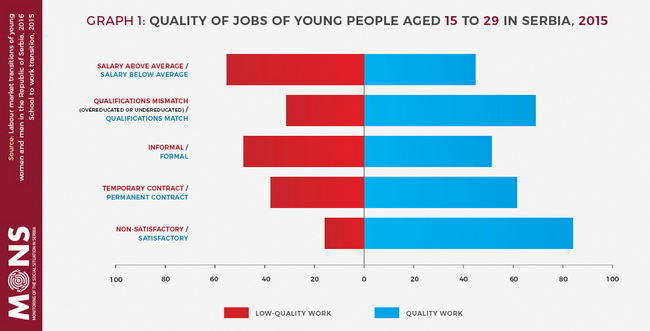

Quality of jobs

A large number of young people in Serbia hold insecure jobs with short-term contracts, working overtime without adequate compensation for overtime, often in the informal sector.

With regard to the type of contract in Serbia, in 2015, about 40 per cent of young people held a temporary contract . It should be pointed out that out of these 40 per cent of young people who had a temporary contract more than half are those with contracts of less 12 months’ duration, which indicates that a large number of young people hold jobs that do not provide security. If we analyse young people with permanent contracts by educational level, we come to the conclusion that most often young people with completed secondary education hold permanent contracts, more precisely 80 per cent of them, while only 10 per cent of young people with tertiary education hold permanent contracts. This data indicates that even higher education does not provide a guarantee that a young person will find a stable job at the beginning of his/her career.

The majority of youth in Serbia work full time: about 55 per cent of young people worked between 40 and 50 hours per week in 2015, and a further almost 20 per cent worked more than 50 hours per week. If it is known that less than half of young paid workers benefit from overtime pay, it can be said that the quality of jobs held by young people is low. Young men are more likely to work overtime than young women.

This low quality of jobs held by young people in the labour market in Serbia is also indicated by the fact that in 2015 45 per cent of the total number of young workers was informally employed . In addition, out of the total number of young workers who were informally employed, four fifths held informal jobs in the formal sector, while the rest was employed in the informal sector. Young people holding informal jobs in the formal sector work either without contract or with a contract such as temporary and casual employment contracts or temporary service contracts that do not provide legal protection and the rights provided by the employment contract. Young people who are informally employed are not paid social and health security contributions or are not entitled to paid annual or sick leave, that would be normally associated with a job in the formal sector.

Even though employees with informal jobs in the formal sectors may work for wages, their contract with their employer (e.g. temporary and casual employment contract, temporary service contract, etc.) does not provide the rights arising from the regular employment contract such as the right to paid annual leave or paid sick leave, overtime, work during weekends, which is the case in the formal employment. All this points to the fact that almost half of the young workers in Serbia hold jobs whose stability and security is low. It can also be noted that young men and youth living in rural areas are more likely to be engaged in the informal employment.

Job satisfaction

Suprisingly, if we analyze satisfaction, despite indications for low job quality, as many as 83 per cent of young people in Serbia in 2015 were satisfied with their current jobs. Obviously, as stated in the report Global Employment Trends for Youth, this seeming contradiction of a young person working in a job that brings little in terms of monetary reward, stability and security claiming job satisfaction, is likely to be a reflection of the optimism of youth and the ability to adapt to realities where so few “good” jobs exist. This is perhaps for the majoirty of youth the value of being employed – any type of employment – outweighs the problems associated with the low quality of the job.

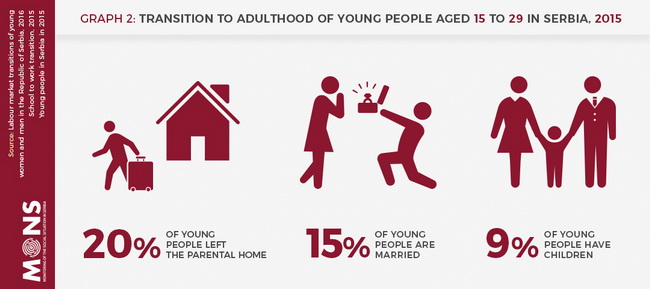

Youth transition to adulthood: How (un)successful is it?

Certain studies, such as Youth – Our Present, emphasize that the transition from school to work is a very important segment of the transition to adulthood, the success of which largely predetermines the success of other segments of their growing up. For example, the family transition depends on the way and pace of the transition from school to finding a job of a young person, which relates to youth decisions on independence from parents, getting married and becoming a parent. As it usually takes 2 years, on average, for a young person in Serbia to find the first stable employment after finishing education , it is certain that such a long transition path will also negatively affect other aspects of growing up. How (un)successful transition from school to work of young people in Serbia is best illustrated by the data that only 20 per cent of young people left their parents’ home. (Un)success is also illustrated by the fact that only 15 per cent of young people are married. Furthermore, the study Becoming a Parent in Serbia concludes that the macroeconomic background sets structural significant constraints to young people on the transition to parenthood, of which unemployment and the labour market flexibility are some of the most significant. The results of the study Young People in Serbia 2015 show that only 9 per cent of young people are already parents, and that 18 per cent of young people do not plan having children in the near future, which is worrying given unfavourable demographic trends and aging of the population. According to this study, the main reasons for the delay of parenthood are connected with a sense of existential and emotional insecurity.

There are numerous explanations for the fact that today almost in all countries youth unemployment rates are higher than overall unemployment rates. Young people not only generally have less specific human capital relevant to a specific firm, but also have lower general skills. In such circumstances, when due to a decrase in demand, firms have to reduce the number of employees, they layoff younger workers first. In addition, young workers may be less efficient in job search activities than adults, as they are likely to have fewer contacts and less experience. They may find themselves in a vicious circle of in(experience) where employers select more experienced workers, thus labour market entrants cannot raise their own experience. On the other side, young people are less likely to have more financial responsibilities than their older counterparts, and their parents may be willing to support them. All mentioned factors may make it difficult to find a job, thus leading to higher rates of unemployment.

Reducing unemployment and creating more and better chances for youth employment are the key challenges facing economic policy makers in Serbia. This is especially important if one takes into account that unemployed young people make up a group that is at greater risk of poverty and social exclusion, and that the unsuccessful school-to-work transition can have unforeseeable negative consequences on other life transitions. In this regard, the identification and removal of the factors that influence the vulnerability of young people should be one of the priorities in creating and implementing measures aimed at improving their position in the labour market. The next article will present the way in which economic policy makers in Serbia response to this position of youth in the labour market, i.e. the programs and measures of the active labour market policy being implemented in Serbia.

Source: mons.rs

Government of the Republic of Serbia

Government of the Republic of Serbia

pdf [271 KB]

pdf [271 KB]

Leave a Comment