Author: Gordana Matković

Author: Gordana Matković

Introduction

This brief overview presents a number of social protection measures undertaken globally and in the Western Balkans in the early months of the pandemic and considers the possible future courses of intervention in Serbia. The consideration of the potential measures that can be undertaken in case of a crisis is significant in view of the likely new wave of virus infections, which may result in the reintroduction of lockdown and similar impacts on the poorest and most vulnerable people. Moreover, since Serbia is also susceptible to natural disasters (e.g. floods), there is the need to also consider the establishment of a flexible social protection system to enable a timely and adequate emergency response.

This publication does not address the measures aimed at maintaining the existing employment level, enhancing social insurance-based benefits or active labour market policies.

Overview of the measures

Based on the World Bank international review of social protection responses to COVID-19 (Gentilini et al., 2020), by 10 July, 200 countries/territories implemented 1,055 social protection measures in the broader sense (social assistance, social insurance and labour market interventions).

The most common type of intervention were non-contributory budget-funded social benefits[1] – 638 measures, or over 60% of the total number. These benefits were provided to more than a billion recipients in 176 countries. More than 70% of the measures were new programmes (454 out of 638 measures), while 79 measures were one-off benefits.

Cash transfers (298) accounted for one half of social assistance programmes. The duration of cash transfer programmes ranges from 1 to 12 months, averaging at about 3 months (according to the data for 71 programmes). The amounts are generous, at 29% of the monthly GDP per capita on average; based on Serbia’s estimated GDP per capita in 2019 (Republički zavod za statistiku, 2020), they amounted to approximately RSD 18,800.

According to earlier reviews, a large number of countries (57) used social registries to expand the coverage of beneficiaries (Gentilini et al., 2020a).

Table 1: Programme types

| Programmes | No. of measures | No. of countries |

| Cash transfers (conditional and unconditional) | 298 | 153 |

| Social pensions | 25 | 22 |

| – Sub-total (cash assistance) | 323 | 158 |

| In-kind food/voucher schemes | 117 | 88 |

| School feeding | 27 | 25 |

| – Sub-total (in-kind assistance) | 144 | 96 |

| Utility and financial obligation support | 156 | 94 |

| Public works | 15 | 12 |

| – Total | 638 | 176 |

Source: Gentilini et al. (2020)

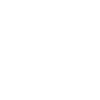

Chart 1. Overview of the improvement of assistance programmes

The overview of all social protection interventions, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO, 2020) is presented in the Table below:

Table 2: Ten most common social protection responses to the crisis

| Programme type | No. of countries |

| Introducing benefits for workers and/or dependents | 214 |

| Introducing benefits for poor or vulnerable population | 199 |

| Introducing subsidies to or deferring or reducing cost of necessities/utilities | 124 |

| Increasing benefit level | 99 |

| Introducing subsidies to wage | 98 |

| Extending coverage | 87 |

| Improving delivery mechanism/capacity | 82 |

| Deferring, reducing or waiving social contribution | 79 |

| Increasing resources/budgetary allocation | 76 |

| Relaxing or suspending eligibility criteria or conditionalities | 52 |

Source: ILO (2020)

In the conditions of limited fiscal space, it is recommended to opt for targeted measures. If the purpose of awarding cash benefits is to boost aggregate demand, it should be clear that the poorer population will surely use these funds for consumption, whereas the better-off can turn a part of it into savings. Hence the recommendation to undertake the measures targeting the poor in that case, too (IMF, 2020).

As indicated in the report of the European Anti-Poverty Network, in the European Union, “many countries are reinforcing income support as short-term measures for those impacted by COVID-19: increasing levels/coverage of minimum income[2] and unemployment benefit levels” (EAPN, 2020, p. 3).

During the crisis, social assistance beneficiaries in the Western Balkans received additional assistance (some municipalities in Bosnia & Herzegovina, Macedonia and Montenegro), amounts twice as high as the regular assistance (Albania), or even higher (Kosovo[3]).[4] Although the amounts of these benefits are typically low throughout the region, and in some cases even provided as a one-off (Montenegro) or limited to certain local governments (Bosnia & Herzegovina)[5], the adequacy of the benefits for the poorest has, in fact, improved.

Table 3: Assistance to recipients of non-contributory social benefits, Western Balkans 2020

| LAST RESORT SOCIAL ASSISTANCE | ||

| Adequacy | Amount | Duration |

| AL | Double amount | During 3 months |

| BA | Additional, in individual municipalities | One-off |

| ME | €50 | One-off |

| MK | €16 (energy subsidy) | 5 months |

| XK | Double + extra €30 the family receives ≤ €100 | During 3 months |

| Extended coverage | ||

| AL | Applicants since July 2019 | |

| MK | Elimination of all criteria except income until the end of 2020 | |

| XK | Households that have not renewed their rights | |

| SOCIAL PENSION | ||

| XK | €30 the household receives ≤ €100 | During 3 months |

| MK | €16 (energy subsidy) | 5 months |

| Extended coverage | ||

| XK | Households that have not renewed their rights | |

| NEW BENEFITS | Amount and target population | Duration |

| AL | €300 to workers laid-off during the crisis | One-off |

| ME | €50 to all registered unemployed non-recipients of social transfers | One-off |

| RS | €100 to all adults | One-off |

| XK – 1 | €130 to households without formal revenue | During 3 months |

| XK – 2 | €130 to workers laid-off during the crisis | During 3 months |

Source: Matković & Stubbs, 2020

Macedonia, Albania and Kosovo also expanded the circle of social assistance recipients (extended coverage). Macedonia has temporarily suspended all eligibility criteria for financial social assistance except the income threshold, effective until the end of 2020 (Влада на Република Северна Македонија, 2020). Albania and Kosovo extended the coverage during the crisis by including those who had applied for assistance in the past year and had been rejected and/or lost their entitlement and had not renewed it (World Bank, 2020; Republic of Kosovo, Ministry of Finance and Transfer, 2020).

The governments of Kosovo and Macedonia also increased the adequacy of social pensions. Same as for social assistance beneficiaries, Macedonia extended social pension recipients’ entitlement to the so-called energy subsidy, which these households usually receive only during the winter, by additional 5 months. In Kosovo, the recipients of social pensions in the amount smaller than €100 per month were entitled to additional €30 during the first wave of the pandemic.

All countries mostly enabled automatic extension of social benefits for the beneficiaries whose entitlements expired during the crisis (including those pertaining to child protection).

Serbia is the only country that has not increased the adequacy or coverage of the programmes targeting the poorest population. A large proportion of the most vulnerable population in Bosnia & Herzegovina has also received no additional financial support.

In-kind assistance

In most of the countries, extremely poor residents of Roma settlements received food or hygiene product packages during the total lockdown, often as part of donor-funded assistance. Deferrals of utility or electricity payments were also a common form of support. There were also examples of local governments providing assistance packages for minimum pension recipients (Belgrade). According to Red Cross reports, soup kitchens have mostly resumed their work throughout the region. The Government of the Republic of Srpska distributed essential food parcels to socially disadvantaged households.

Many governments also introduced new (mostly one-off) cash benefit schemes, intended for the unemployed (Albania, Montenegro, Kosovo) or even for all citizens (Serbia). Serbia is one of 5 countries in the world[6] that awarded cash assistance to all adults in the amount of €100, but not until the lockdown was lifted. The total expenditures on this purpose amounted to 1.3% of the 2019 GDP. The administrative solutions for applying and payments were very efficient.[7]

Kosovo made an effort to also include households that generated income solely in the informal economy. During the three months of the pandemic, a new programme was introduced, open for applications by all households that did not have any income from formal employment or payments from the budget. The application procedure was simple and required only a statement by heads of households, and the amount of the assistance was €130 per month (Republic of Kosovo, Ministry of Finance and Transfer, 2020).

A part of the assistance also targeted the recipients of social insurance-based benefits. For instance, during the state of emergency in the first three months of the pandemic, one-off assistance was awarded to all pensioners in Serbia (€35) and to minimum pension recipients in Montenegro (€50). More favourable indexation and new ceilings for minimum and maximum pensions were introduced in Albania. Albania also doubled the amount of unemployment benefits, while Macedonia relaxed the eligibility requirements for this benefit for persons who lost jobs during the pandemic.

It strikes the eye that, despite their above-average vulnerability, families with children did not receive additional support, although most countries have means-tested child allowance schemes. Overall, families with children in Serbia received smaller benefit amounts compared to families without children, since only adults were entitled to universal cash assistance, while the only other assistance was awarded to pensioners. Unlike pensioners and FSA recipients who received the universal cash assistance automatically, adult members of child allowance recipient families had to apply for it. In other words, although the information system includes records on them and in spite of the evidence of their vulnerability, poor families with children could not enjoy this little privilege, either.

In most of the countries, the families living in substandard and overcrowded Roma settlements did not receive sufficient support and there were also reports of discrimination.[8] In Serbia, under the pressure of non-government organisations, cisterns with drinking water were provided for Roma settlements, and households whose electricity supply was disconnected due to unpaid bills were reconnected to the supply system.[9]

Summary of cash and in-kind social assistance in Serbia

The majority of the measures in Serbia were aimed at the prevention of joblessness and the support to small and medium-sized enterprises. As part of the social protection efforts, cash assistance was awarded to pensioners (€35) and, after the state of emergency was lifted, to all adults in Serbia (€100). Social benefit recipients’ entitlements were automatically renewed, and electronic applications were also enabled. Some local governments distributed assistance packages and, with UNICEF’s support, humanitarian aid was provided to a number of Roma settlements. Several local governments enabled deferred payment of public utility bills and desisted from enforcing debt collection during the state of emergency, while Elektroprivreda Srbije announced that it would not charge an interest on overdue electricity bills.

Responses in the field of social care services, either residential or in the community, were primarily restrictive in nature (prohibition of visits, cessation of operation), resulting in the further decrease of availability of the services, which were not very prevalent in any of the Western Balkan countries in the first place.[10] While the coverage decreased, the demand for the services dramatically increased, especially during lockdown.

Support to some population groups, such as homeless people, was missing altogether.[11] The impact of the crisis on other specific groups has not been documented (e.g. victims of trafficking, drug abusers or prisoners).

Since schools, day care and personal attendants ceased to work, children with disabilities were left with no support outside of their family circle. There are also indications that the number of domestic violence victims has increased across the Western Balkans.

In some communities, the number of volunteers increased as the services were temporarily halted. Paradoxically, day care and home care services were suspended and the role of accredited direct service providers was entrusted to volunteers, often with no detailed background checks. According to various sources on the internet, support via telephone, Facebook and web-based platforms has expanded. In the beginning, there were also problems with the issuance of travel permits for professional workers, as well as for family members and informal service providers.

Extensive effort was dedicated in Serbia to protecting the beneficiaries of residential care institutions and a large number of measures addressed the functioning of residential homes.[12] Local governments were required to ensure the functioning of the most prevalent non-institutional service – home care, in compliance with the decision of the competent ministry.[13] In reality, the service seems to have been only partially functional in many communities due to the suspension of public transport, the fact that home care professionals were taking sick leave, and even for fear in the beginning.[14] Day care centres for children with disabilities were closed; however, some institutions organised communication with the beneficiaries via telephone and Facebook.[15] The personal assistance service was mostly provided smoothly, although there were difficulties in obtaining travel permits.[16] Some communities also experienced problems in the functioning of the personal child attendant service.[17]

Potential measures in the time of crisis

I Cash transfers and benefits

The review of strategic choices, suggestions and practical measures shows that the recommended response in crisis conditions is primarily the expansion of the existing means-tested programmes, in terms of both the increase of benefit adequacy (vertical) and the increase of the coverage of beneficiaries (horizontal).

1. Increasing the amount of the benefits awarded to existing beneficiaries, according to the poverty criterion

The increase of benefit adequacy/amount in Serbia would apply to:

a) Financial social assistance recipients

Increased amounts during the crisis would certainly be justified, considering that the nominal current benefit amounts are inadequate and insufficient to ensure subsistence and lift the beneficiaries out of poverty (either absolute or relative).

An important thing to note in that regard is that there is no need to assess the impact of benefit levels on the recipients’ motivation to get and keep a job, given the dramatic decline of demand for labour and the increase of unemployment.

During the pandemic, poor FSA recipients could not rely on the usual coping strategies, such as remittances from abroad, as their amounts decreased, or they were largely cancelled. During lockdown, their engagement in the informal economy was also impossible, including seasonal work in agriculture, which is a source of additional income for social assistance beneficiaries. During the state of emergency, additional assistance was also reduced in some local communities, while the closing of educational institutions meant that free snacks in schools and kindergartens were no longer available.

Furthermore, the poorest households clearly have no savings and, as the entire population also struggles at the same time, they have nobody to borrow from, while on the other hand they are facing additional expenses for the purchase of masks, hygiene products, non-prescription medications etc.

b) Child allowance recipients

In Serbia, child allowance is awarded to poor families with children subject to a means test. The income ceiling for child allowance is only slightly higher than the ceiling for FSA and is approximately equal to the relative poverty line.

Families receiving child allowance also had no access to the usual coping strategies, and some parents who had possibly worked in temporary and casual jobs may have lost their jobs and the source of income, as well.

Increased expenses are reasonable justification for awarding increased benefits in this case, too. Especially considering that, according to the SILC 2018, 40% of Serbia’s population assessed that the households they lived in could not face unexpected financial expenses in the amount of RSD 10,000.[18]

2. Extending the coverage of means-tested social benefits – inclusion of new beneficiaries

When a crisis hits, it is generally believed that inclusion errors are less of a problem than exclusion errors and that the response time is crucial. In other words, it is more important not to exclude people who need assistance and to ensure that they receive it while the crisis is still ongoing.

In Serbia, the coverage of the poor by the FSA scheme according to the absolute poverty criterion is not full and, theoretically, reaches approximately only 50% (Vlada Republike Srbije, 2018). This shows that a large number of individuals who are unable to meet their basic needs do not receive assistance and, in times of the overall crisis, they are also unable to avail themselves of other coping mechanisms. Moreover, a considerable proportion of the population lives just above the absolute poverty line, as indicated by the data on poverty line sensitivity (Tim za socijalno uključivanje i smanjenje siromaštva Vlade Republike Srbije, 2019).

A potential quick expansion of the beneficiary circle could include:

- Households with the status of vulnerable energy customers, which are also poor and to which the entitlement is awarded subject to a means test (except the ones receiving FSA and child allowance and the same time);

- Households that had applied for FSA and had been rejected just before the crisis hit, which fulfilled the income criterion (but, for instance, failed to meet the asset ownership criterion), or had been rejected for exceeding the income ceiling by a very small amount;

- Temporary inclusion of all those who appealed against the rejection of their applications;

- Long-term FSA recipients who lost eligibility for failing to meet the workfare requirement;

- Recipients of one-off cash benefits at the local level in the past year, possibly according to a quota assigned to the particular local government, in conformity with Article 110 of the Law on Social Protection, which provides for the transfer of funds from the Budget of the Republic of Serbia to local governments for the purpose of awarding one-off benefits in cases of serious threat to the living standard of a large number of people;

- Families that have applied for child allowance and those that have lost eligibility due to child’s irregular school attendance, or children who have just attained the age of majority;

- The Roma living in substandard Roma settlements (area-based targeting), through the inclusion in the child allowance scheme without a means test.

3. Additional remarks, regulation and organisational issues

In view of the possible prolongation of the crisis, in addition to short-term measures, it is sensible to also consider the relaxation of eligibility criteria for both FSA and child allowance in a longer term, especially those related to the asset ceiling and the requirement to participate in workfare schemes.

Other solutions to be noted certainly include automatic renewal of entitlements for existing beneficiaries, as has already been done, and simplified application procedures for new beneficiaries. It would be useful to define these procedures accurately, optionally with a list of documents that can be submitted subsequently, or with a provision that the amount of the awarded benefit will be reduced if there are no records proving that the applicant has received social benefits before etc.

Another possible option to consider is the award of one-off benefits to households that receive no assistance from the state, if none of the household members are employed in the formal sector and receive no social insurance-based benefits.

It would be especially important to explore new payment modalities, which have developed quickly in many countries, as they can prove to be crucial during lockdown and in situations when banks are closed for new clients for several months (Una et al., 2020). Mobile cash or electronic transfers in the form of e-vouchers for food and hygiene products would solve serious problems regarding the distribution of in-kind assistance or the risky functioning of soup kitchens.

For certain target groups, such as homeless people, it is necessary to make plans for the distribution of food parcels at predefined locations, with no contact with the beneficiaries.

The establishment of an information system (social registries), which has served as an important source of the data on vulnerable individuals and families in many countries, is undoubtedly essential for ensuring better preparedness of the social protection system for future crises.

A new law on social protection should definitely provide for the possibility of and specify the method for scaling up the financial social assistance entitlement automatically in crisis conditions, in both vertical and horizontal sense. This type of amendment should also be introduced in the Law on Financial Support to Families with Children, with respect to child allowance.

An emergency like the current one caused by the hazards associated with the spread of COVID-19 is another warning that the unacceptable living conditions in Roma settlements have to be addressed.

Finally, for each of the discussed social safety net expansion scenarios there are also financial impacts to be considered, in order to ensure that any choice also takes into account the fiscal burden.

II Social care services

The most important measures in the area of social care services certainly include the increase of the number of beneficiaries and adaptations of the regulatory and organisational aspects.

The expansion of beneficiary coverage is especially important in lockdown conditions, while the potential new beneficiaries are:

- elderly households (all members aged 65+),

- households consisting of elderly members aged 65+ and persons with disabilities,

- households consisting of one or more persons with disabilities, irrespective of age,

- households in remote rural/mountainous regions that are cut off after the public transport is shut down or drastically reduced,

- single parents with children with developmental and other disabilities

- households in which all members are in self-isolation,

- children of parents who are ill or hospitalised with COVID-19, or suffer from other health problems,

- victims of domestic violence, migrants and homeless people who have not used the services before.

Local governments, which are responsible for the majority of non-institutional social care services, should first prepare and/or review their emergency response plans. They should be especially prepared for ensuring the functioning of the services in periods of restricted or entirely prohibited movement, e.g. by:

- initiating the registration of the households that may need support in extreme circumstances,

- creating lists of volunteers and launch their background checking and training (e.g. in cooperation with the Red Cross),

- preparing generic lists in order to enable quick and efficient issuance of travel permits to members of certain vulnerable groups and to individuals caring for them.

At the national level, all measures undertaken in residential care institutions should certainly be analysed, and this activity has already been launched in cooperation with the World Health Organisation.[19] The critical review should particularly focus on the performance of the control function, considering that some institutions failed to follow the instructions, which resulted in tragic consequences.[20] Emergency response plans of most institutions should be reviewed.

It is also necessary to formulate new temporary standards and reorganize the home care service, which is certainly essential for both the elderly and persons with disabilities in the conditions of prohibited movement and reduced number of caregiving staff (provision of only the essential food items and the delivery of medications to the front door without entering, increased number of beneficiaries per elderly caregiver and so on).

It would be meaningful to also review the standards of other services and, in particular, to consider the possible operational modalities of day care centres for children and youth with disabilities. The fact that the professional staff of these institutions are capable of also carrying out other duties during the crisis (similar to personal assistants, organisation of open-air workshops, taking beneficiaries for walks and so on) should not be overlooked. In partnership with special schools, day care centres could also prepare special television programmes following the models that are successfully implemented in the education sector.

It is especially important to determine the extent to which the crisis has contributed to the increased rate of introduction and usage of new technologies in the provision of counselling and essential information. These experiences should be analysed and integrated in the daily mainstream practices in non-crisis conditions. In cooperation with local governments, training should also be launched at the national level for professional workers, and even for volunteers for specific purposes, in online and telephone counselling.

The collection and sharing of good practices at the local level would also clearly be valuable for disseminating ideas and experiences that have the potential to upgrade social protection in extremely difficult circumstances for the most vulnerable groups.

Emergencies and crises also clearly demonstrate the significance of the cooperation and coordination among different levels of government and sectors. In addition, they distinctly indicate the necessity of cooperating with non-government organisations working directly with vulnerable groups, which have managed to respond quickly, lobby for the resolution of the most critical problems, as well as to propose solutions themselves.

References

- EAPN. (2020). Putting Social Rights and Poverty Reduction at the heart of EU’s COVID-19 Response. Accessed on 19 May.

- Gentilini, U., Almenfi, M., Dale, P., Lopez, A.V., & Zafar, U. (2020). Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19: A Real-Time Review of Country Measures. World Bank “Living paper” version 12 (July 10, 2020). Accessed on 25 June.

- Gentilini et al. (2020a). Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19: A Real-Time Review of Country Measures. World Bank “Living paper” version 10 (May 22, 2020). Accessed on 25 May.

- ILO. (2020) Social Protection Responses to the COVID-19 crisis around the world. Accessed on 19 May.

- IMF. (2020). Expenditure Policies in Support of Firms and Households. Accessed on 19 May.

- Matković, G. & Stubbs, P. (2020). Social Protection in the Western Balkans: Responding to the COVID-19 Crisis. Center for Social Policy &The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Dialogue Southeast Europe. Accessed on 20 July.

- Republički zavod za statistiku Srbije. (2020). Statistički kalendar Republike Srbije, 2020.

- Republic of Kosovo, Ministry of Finance and Transfer. (2020). Operational Plan on Emergency Fiscal Package. Accessed on 20 July.

- Tim za socijalno uključivanje i smanjenje siromaštva Vlade Republike Srbije. (2019). Ocena apsolutnog siromaštva u Srbiji u 2018. godini. Accessed on 15 May.

- Влада на Република Северна Македонија (2020). Уредба со законска сила за примена на законот за социјалната заштита за време на вонредна состојба. Службен весник на РСМ, бр. 89 од 3.4.2020 година. Accessed on 20 June.

- Una, G., Allen, R., Pattanayak, S. and Suc, G. (2020) Digital Solutions for Direct Cash Transfers in Emergencies, IMF. Accessed on 10 July.

- Vlada Republike Srbije. (2018). Treći nacionalni izveštaj o socijalnom uкljučivanju i smanjenju siromaštva u Republici Srbiji – Pregled i stanje socijalne isključenosti i siromaštva za period 2014–2017. godine sa prioritetima za naredni period. Beograd: Vlada Republike Srbije.

- World Bank. (2020). Albania adjusting social protection to mitigate the effect of COVID-19 on poverty and vulnerability.

- Law on Social Protection, Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, No 24/2011.

***

The analysis “Social Safety Nets in Times of the Covid-19 Crisis” is available for download in .pdf and .docx format.

———–

[1] Social assistance, according to the World Bank terminology.

[2] An equivalent of financial social assistance – a benefit awarded subject to a means test, often also referred to as the guaranteed minimum income.

[3] This designation is without prejudice to positions on status and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

[4] The experiences in the Western Balkans are written based on Matković & Stubbs (2020). Social Protection in the Western Balkans: Responding to the Covid-19 Crisis. Center for Social Policy & The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Dialogue Southeast Europe.

[5] More information available at: starigrad.ba; www.centar.ba

[6] Others were Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore and Japan.

[7] More information available here and here

[8] More information available at: www.rcc.int

[9] More information available at: www.coe.int, as well as at: www.a11initiative.org

[10] According to Matković & Stubbs (2020).

[11] According to reports by the “Krov nad glavom“ association, even the public toilets were closed in Belgrade during the first three months of the pandemic. Online conference on “Poverty during the Covid-19 pandemic and in post-crisis period in the Republic of Serbia”. More information available at: socijalnoukljucivanje.gov.rs

[12] More information available at: www.minrzs.gov.rs

[13] More information available at: www.minrzs.gov.rs

[14] More information available at: www.novosti.rs

[15] More information available at: www.rts.rs; ilovezrenjanin.com

[16] More information available at: www.cilsrbija.org

[17] More information available at: ilovezrenjanin.com; www.ozonpress.net; studiob.rs

[18] Eurostat database. Table Inability to face unexpected financial expenses – EU-SILC survey [ilc_mdes04]

[19] More information available at: www.minrzs.gov.rs

[20] More information available at: www.minrzs.gov.rs

Government of the Republic of Serbia

Government of the Republic of Serbia

pdf [271 KB]

pdf [271 KB]

Leave a Comment